Universal Design for Learning: The Recognition Network

All students bring unique perspectives, approaches, experiences, preferences, learning styles, and, in some cases, disabilities to their courses. Addressing this wide variety of characteristics presents a considerable challenge for online instructors. How can we design our courses to address the preferences and accessibility needs of all our students?

That’s where Universal Design for Learning (UDL) comes in. UDL is a course design framework centered on providing all students in the course with an equal opportunity to learn, acknowledging that all students don’t learn the same way, and encouraging instructors to allow students the freedom to customize their learning path based on individual need and preference.

UDL asks the instructor to think about three different brain “networks” (CAST, 2014):

- Recognition network: Collects information and puts it into meaningful categories

- Strategic network: Plans and performs tasks

- Affective network: Manages motivation and engagement

In this article, we’ll address the recognition network. This particular network invites thinking about instructional materials and encourages a diversity of approaches that can address accessibility issues before they arise and reach a wider variety of student learning styles.

Provide a Variety of Instructional Materials

Think about all of the ways that you communicate to the students in your class and the different ways you represent important ideas and concepts. It’s likely that you have methods that you often rely on, whether textbook readings, infographics, or video lectures, and you’re comfortable with them because they work well when you’re trying to organize your thoughts or teach something new. Students have similar preferences for how they learn.

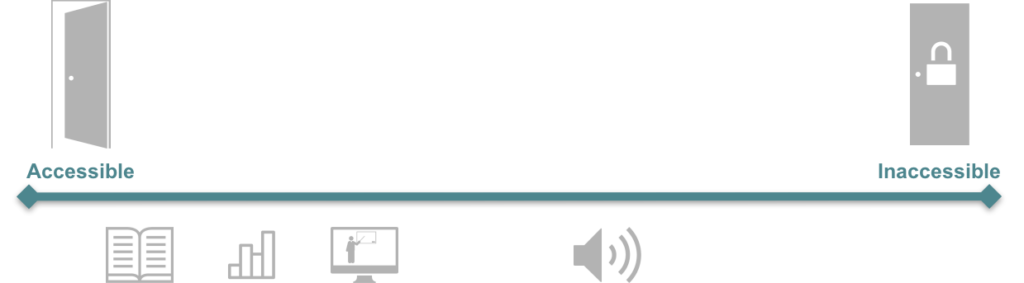

Imagine that all of the content in your course exists on an accessibility spectrum. At one end, you have course content that’s absolutely perfect in its ability to communicate ideas to learners, and at the other end, you have content that’s entirely inaccessible. What’s important to realize is that not only does the accessibility of the content vary depending on your objectives, but each piece of content occupies a different position on the spectrum for each student.

Well, the good news is that at least some of your course content is likely at or very near to the fully accessible end of the spectrum for many of your students. Unfortunately, there’s also a distinct possibility that you have content in your course that exists at the completely inaccessible end of the spectrum for some learners. For example, if you’re relying on lectures as the primary method of communicating concepts, students who aren’t able to hear could find your content inaccessible.

Most students in your class don’t represent the extremes of the spectrum, but rather fall somewhere in the middle. In addition, sometimes students have physical disabilities or cultural experiences that lead to a preference (rather than a need) for one representation style over another. For example, a dyslexic student can still read, of course (albeit at a slower pace than many of his or her fellow students), but he or she may prefer to watch a video rather than read a document. So it’s possible that your course content may be accessible, but not ideal.

So how do you go about representing your course content so that it meets the needs and preferences of all of these different learners in your classroom?

One answer to this is variety. Let’s think about an online history class focused on identifying key battles in the Revolutionary War. Text works great for students who prefer to read, but you could also include an audio recording in which you present each battle and discuss its significance. Include a transcript for this file, and it can help support students who prefer auditory or visual input. You might also have a video that uses animations or a chart that organizes key battle statistics.

You can use all of these methods to present essentially the same information, but when you present them all together, learners can choose a mode of representation that best suits them. You’ll find that some students have a clear preference for one over the other while other students use a combination of formats. By offering choices, you’re allowing them to select the best path for themselves.

Be sure to explicitly present these multiple formats as a way for students to identify their preferred method of learning, and encourage experimenting with each of the different formats. Not only will your students have the opportunity to engage with your course material in a way that works best for them, but they’ll also better understand how to identify and support their learning preferences and needs in other environments.

Identify and Define Discipline-Specific Vocabulary

The next thing to consider is vocabulary. Think about international students for a moment. Although they have likely demonstrated competency in the English language through some method of standardized testing, the fact is that many instructors teach in areas that have a unique set of terms that foreign students might find difficult to understand. One way to assist these students is to highlight discipline-specific words in written formats, and link these words to an online dictionary that allows students to hear the word pronounced correctly and see its definition. During any spoken presentations, take time to focus on correct pronunciation and clearly explain the definition of the word. Creating a glossary specific to your course is also a helpful step.

Highlight Context, Narrative, and Patterns

You should also think about how you intend to link individual topics into a single overarching lesson. It’s easy to assume that your learners will be able to see how concepts fit together to form a bigger picture, and it is true that some students do use processing strategies that support this type of learning. Most novices, however, tend to learn concepts in isolation from one another, and need help to connect them. Include links and references to earlier lessons to reinforce connections and highlight the narrative arc of your course. Generate module introductions that:

- Review (Activate prior knowledge.)

- Preview (Discuss the upcoming module topics and objectives.)

- Motivate (Make real-world connections or underscore the importance of the material.)

For students who prefer graphical representations of how ideas interconnect, consider including a concept map and illustrating where links and connections exist.

Whenever patterns exist within a concept, it’s important to intentionally identify them. Drawing boxes and underlining areas of repeated actions or formulae within a series of math problems, for instance, helps students see the pattern that they may not have noticed on their own.

Conclusion

Universal Design for Learning is based on the idea that all students learn differently. To address the differences in recognition networks, instructors should include multiple ways of presenting course material, ideally in verbal, text, and graphical forms. Provide opportunities for students to learn new vocabulary rather than assuming students will understand based on context. Be sure to reinforce the course narrative by illustrating how each part fits into the whole. And when patterns exist within content, take time to point them out and explain them.

It’s true that these practices may require some additional work on your part. But remember, the time that you spend developing these alternative pathways and helpful resources will make your teaching more impactful as you encourage students to discover the best ways they can learn.

References

CAST. (2014, November 12). UDL guidelines: Theory & practice. Retrieved from http://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl/udlguidelines_theorypractice